Inland Empire (Review)

"A painted picture is like a vehicle. One can either sit in the driveway and take it apart or one can get in it and go somewhere." - Mark Tansey

That's exactly how I approach comments on David Lynch's Inland Empire, not by taking it apart but by assessing the destinations indicated. Lynch has claimed the film is easily understood, that the story is straightforward. I agree. I'll examine two prevalent themes within the mechanics of the film, and suggest how these themes constitute a destination, or thesis, for Lynch.

I don't believe a close reading assists this approach, so these comments are drawn from a single, uninterrupted viewing, which was not repeated. I'm verifying no observations from the film itself.

The Theme of Projection

The opening image of the film appears to be as much a diagram of the film as it is a title card: a veiled and smokey shaft of light--perhaps from a film projector, perhaps from a spotlight. It opens from frame right and slowly illuminates the film's title.

Indeed the work as a whole feels like a projection. Like the visible shaft of light, the projection is at a distance and immaterial from the image it produces; the bulk of the film may merely be a preparation for a final image, a slowly rendered illumination. True to Lynch's form in recent films, the film willfully tests the patience and attention of the viewer, particularly in the first third of the work, when even a deliberately passive viewer is obligated to index the various locations, characters, and situations that appear, disappear, and reappear, freely interlaced. I came away with the impression that the bulk of the film was form (or formula) intended only to set the stage for a final reconciliation. Similar communions occur in other Lynch films, most notably in the final moments of Blue Velvet and Muholland Drive. Sometimes these occur between people, sometimes between ideas. Those films have more substantial narratives that preceded the communion. Inland Empire does not, and in that sense it feels at once more concentrated and less focused, as if Lynch's basic formula is visible, swirling about, poorly dissolved in conventional film form.

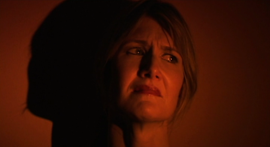

Tiny versions of this larger projection are everywhere: many characters watch other characters, often with no direct dialogue or other interaction. This surveillance is often mirrored by various parties watching television. There is also quite a bit of gazing into and out of domestic interiors of various stripes. Laura Dern's multiplicioutous character1 is at one point instructed to burn a hole in a woman's slip and to look through the aperture, another form of projection. There is of course the film's lighting, wherein deliberate shadows are framed more carefully that the subjects that cast them. Most potently, there is the spotlighting, another frequent objet Lynch, most obviously used in Twin Peaks. Dern is often forced to stare into a dim circle of light, or is being tracked by search light. Most often what she seeks is what appears to be casting the light, but her seeing with critical exceptions is an apparently confused act of desperation, not dialogue.

Toward the end of the film, Laura Dern's character confronts her own projection, presumably her work in her own film2. It is this act, and the moments that follow it, that I believe establish the core of the film's inquiry around the cognitive experience of acting, that is what it's like to project art onto one's self. The moments that follow this confrontation deserve special focus.

Force of habit--or a steady diet of traditional narrative--encourages us to identify strongly with the first few characters and locations. That is what we do when the film opens with an apparent negotiation between a prostitute and a client for sex. Several disjointed minutes later, we observe a sitcom--in many ways a live-action cartoon--of humanoid rabbits. Their movements, the staging, and most obviously the laugh track suggest this is a sitcom of sorts, watched by a crying woman, quite possibly the prostitute from the opening sequence.

Periodically, we return to her experience, and at times it seems she may be watching Dern's odyssey. Dern will at one point make a partial appearance in that world. Not long after Dern confronts her own image on film, a powerfully cool, blue projection light is featured. The camera is pointed directly into it. I believe this can be read as the origin of the projection, a terminal or singularity (read these words any way you wish) through which Dern--or perhaps more accurately Dern's characters--pass. In keeping with Lynch's conscious use of video throughout, it could also be seen as the electro-magnetic energy of a cathrode-ray tube. This image is followed by Dern's encounter with the television-watching prostitute: the prostitute is first presented watching herself on the television; Dern appears from the hallway in something resembling a kind of Annunciation; they kiss without passion and Dern vanishes, leaving her viewer, the prostitute, apparently transformed.

The Theme of Interior

The choice of standard definition video as a production format is surprising. Surely Lynch can afford to shoot on film. Of course Lynch has become increasingly adroit with web-based production and distribution, wherein he's made effective use of video post-production and the petty capitalism of the web. Yet for this "big screen" project, Lynch may have been drawn to the flattened conventionality of this format. Compositions have the same saturated color and unconscious lighting as an America's Funniest Home Videos living room.

Lynch seems to relish the stripping away of glamour here. And glamour has been resident in the staging and photography of a lot of his work. Mulholland Drive in particular seemed to relish the skylines and bustlines of the hyperconnected amplifications of 1950's Hollywood and pre-millennial Los Angeles. Lost Highway too had the costuming and gloss of pulp novel cover art. This glam was particularly apt for the thematic optics through which Lynch works: the beautiful contrasted with the grotesque, a hollow protagonist mirrored in dark, menacing conversations with themselves, lush theaters, stages, screens, and other locations of projection.

Of course, video only increases how the interior lighting in Inland Empire feels found. Many of Lynch's compositions favor the form over the actor, presumably underscoring the idea that the artifice of the act of acting is itself under examination, and not just the usual byproduct of filmmaking. In this way, the spaces, shadows, and arrangements Dern and her pursuers and paramours move through feel like the clips pinning a slide under the microscope.

Sequences in the film cut in quite early, ahead of any human activity, and late in scenes, we often feel like we've overstayed our welcome. These interiors--most acutely the suburban home, which would at once appear to be in Poland, the Inland Empire region of Southern California, and on a Hollywood backlot--take on a potent symbolic role in describing the cognitive or emotional state of their residents. There is a sense that in the (self?) manipulated psyche of Dern's acting, locations like the suburban kitchen, the Hollywood Walk of Fame, and her "character interrogation" dictate the terms of the experience, much more than anyone she may be observing or any action she may be taking. Often, one of the layers of Dern's character3 appear immobilized, in a trance, reading, never writing, locked in a gaze with themselves or their actions.

This idea of surrounds as a mental prison is present in the photography of Gregory Crewdson.4 His carefully crafted "film still" photographs generally depict the dreadful collision of the extraordinary and the mundane. Often it is some abstract and alien idea gone to seed in the mind of a photographic subject, awake and alone in a sort of self-consciousness, beyond twilight or perhaps near dawn, confronting something within themselves. Some of his earlier work does not feature human models, but recalls Lynch imagery from Blue Velvet, of rotting human flesh found in nature, or animals as props in an essay on the layers of human experience that sum up civilization.

Crewdson's compositions are often predicated on the idea that the American domus is a crumbling edifice wishing to keep the outside out and the inside in, an insulation that is most tenuous at twilight, when windows become mirrors, temperatures change wildly, and the waking pass into sleep. Crewdson's subjects are almost always depicted alone, in repose, and surrounded by their strange circumstances. Those might be the penetration of the bedroom by a tree-trunk, the flooding of a living room, or the deliberate recreation of nature (flowers, turf, soil) in a kitchen or garage. There are many film touchstones here, Hitchock and Speilberg chief among them, but when it comes to the design of the interiors, Crewdson walks the same knife edge as Lynch: the furniture and lighting is conventional but menacing, upholstered plainly, and stuffed with discontent.

The Explosion of the Actor

These themes point to a central argument. The inquiry for Lynch in Inland Empire is acting. Some of it is projection--into another mind, another world--the wearing of a mask. Some of it is the mere act of moving through an interior, the passage through a mask as architecture, or an artificial nature.

Mulholland Drive contains an important scene in which Lynch demonstrates the magic of acting. Naomi Watts' Betty rehearses before her audition and the result is wooden, the words are nothing more than speech. She is not working with an actor and no psychological transformation occurs. Moments later, we slowly run through the words again, only in her audition with an experienced actor the words come alive, it's as if she's lived what the words dictate.

Inland Empire appears to be an explosion of that idea. Lynch is preoccupied with the cognitive confusion of falling into a role to such an extent that the mirrored boundary between a character's fiction and an actor's craft is shattered. Dern's character wins a role, begins auditions, and becomes trapped in the set5, achieving escape it would seem only through transformation. And the transformation is not Dern's, it belongs to her desperate viewer--the "woman in trouble"--the woman who watches television and is visited by the resolute Dern late in the film.

Put simply, Lynch is presenting the painful sacrifices actor demands to produce their product. The product is pathos.

As the Film Relates to Mulholland Drive

We must be approaching the tenth anniversary of the initiation of Lynch's Mulholland Drive project. A wonderful New Yorker article from 19996 outlines this tragedy of television development. For those who knew that backstory, the feature film, released in 2001, seemed a bad fit, roughly edited and rushed to an ersatz climax. The threads that Lynch had carefully created in the concept were so loosely knotted in the feature format that it echoed Twin Peaks: Fire Walk with Me, a two-hour condensation of the ABC prime time soap opera: a pastiche of curious symbolism and mystical transformation, and easily Lynch's weakest feature.

Imagining what Mulholland Drive would have been like given the time to unfold that two seasons of Twin Peaks enjoyed is a fun mind game. Since ABC cancelled the pilot in 1999, The Sopranos, The Wire, and a host of other television shows have suggested that there is an audience for the complex, challenging supranarratives that Lynch produces. He works best when working against the grain of a medium or genre. This was the means of production for Twin Peaks to produce great television. It would have been nice to list Mulholland Drive in that company, producing hours and hours of text for active viewers to scale, seeking forms, context, authority in ambiguity.

Inland Empire works as a film because the balance between text and reader is wonderfully unbalanced, to the degree that the viewer can feel a bit like the "woman in trouble." The initiative holds the same interesting combination of convention and complexity in a typical Mark Tansey painting, wherein there is a massive amount of photographic detail, quite conventional, reshaped into a classical form, pointing to some distant aim, usually a cosmic joke at the expense of art history.7

Notes

1. It's difficult to write about the characters in this film in good faith because it's so hard to be certain about identity and filmmaker intentionality. Suffice it to say, Laura Dern's primary character, an actress who is visited early in the film by a neighbor, goes through several layers of identity. These at times are presented as character research, traditional film acting, and journeys within. Suffice it to say it's hard to write about without feeling a little lazy since I didn't take the time to create a taxonomy for the above.

2. This moment in the only in the film that appears to depict film, as opposed to video image.

3. In this mode, Dern seems to be attempting to identify with her character, or what her character may have accidentally become. Her time with the prostitutes be exemplify this. It's difficult to say if Lynch is suggesting that acting itself is a form of prostitution.

4.

Gregory Crewdson, Untitled, part of the Twilight series, 1998-2002.

5. I didn't have time to do a careful assessment of the set as we see it early and late in the film, but there may be a lot of useful details in the evolution of the backlot to the "Inland Empire" house to the Hollywood Boulevard set.

6. Tad Friend, Annals of Entertainment, "Creative Differences," The New Yorker, September 6, 1999, p. 56

7. Take "Close Reading" for example.

Posted October 19, 2008.